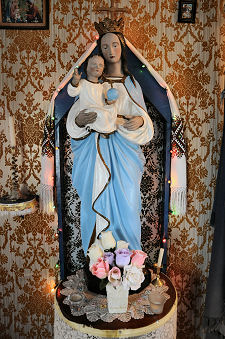

Inside the Chapel, 2013 |

Beside a minor road a mile and a half south of Lockerbie stand a few weatherworn prefabricated huts. They are all that remains of the Hallmuir Prisoner of War Camp. Brown tourist signs from the edge of Lockerbie help visitors find a destination that could otherwise be hard to find. The reason for seeking out the site can be found in one of the huts which, though completely unremarkable from the outside, houses the superb Hallmuir Ukrainian Chapel, built here by Ukrainian internees who occupied the camp from May 1947.

We visited and took photographs of the chapel in 2010 and 2013. We later heard from visitors who had found it closed. News reports in May 2022 suggested that funding had been secured to help safeguard the future of the chapel after a period of closure and we revisited to see what had changed in February 2023.

We found that a new roof had been fitted. The building was locked but we got the sense by peering through windows that the interior had been redecorated with fixtures and fittings stacked or boxed and ready to resume their rightful places.

We also wondered if the surrounding area had lost some trees and bushes since our previous visit (though it was February), and the vehicle business immediately to the north-east seemed to encroach more closely on the chapel. This impression was given force by whoever greeted us by driving a very old bus round and round the site using the roads both sides of the chapel and part of the public road to create an oily smokescreen that lingered for some time.

Hopefully the chapel is turning a corner and can look forward to a more secure future. If you have any information about this, we'd very much like to hear from you. Photographs on this page are from all three of our visits. (Continues below image...)

Exterior View of the Chapel, 2023 |

There are inevitable parallels to be drawn between the Ukrainian Chapel at Hallmuir and the Italian Chapel on Orkney. but apart from the obvious fact of their being separated by most of the length of Scotland, the main difference is simply that the Ukrainian Chapel is much less well known than it deserves to be.

Another difference is that the story of the Ukrainian Chapel is much less clear than you might expect of events that took place within the memories of some still alive to talk about them. We've taken as the basis of our account of the camp and the building the Historic Environment Scotland document which led to the building being listed, and drawn on other contemporary accounts for the story of those who created the chapel in the form in which you see it today.

The Hallmuir Prisoner of War Camp was built here in 1942 to house up to 450 German and Italian prisoners. The building which later became the Ukrainian Chapel was first used as a place of worship by Italian prisoners during their stay at Hallmuir. By 1947 the camp stood empty following the repatriation of the Italians.

Four years earlier, in 1943, volunteers and conscripts from German-occupied Ukraine had been formed into a military formation, the 14th "Galicia" Division of the Waffen-SS, largely serving under German officers. There was nothing unusual about this: similar SS military formations emerged at the same time made up of men from other occupied countries in both eastern and western Europe. The main attraction for the Ukrainian volunteers was a judgement by some that the long standing struggle for Ukrainian independence was more likely to succeed under the Nazis than under the Soviets. The fact that the Nazis named the division after Galicia, an ancient region covering parts of Ukraine and Poland, rather than using the more politically sensitive name of "Ukraine", suggests independence was unlikely whoever won: but despite that, many Ukrainians saw the Soviets as the greater threat to nationhood.

For the next two years the 14th Division fought alongside other German units against Soviet forces and partisans in various parts of the eastern front. March 1945 found the division trying to hold off advancing Soviet forces at Graz in Austria: its "rebranding" in the middle of that month as the 1st Division of the Ukrainian National Army had little practical impact. What was left of the division surrendered to British and US forces on 10 May 1945, and the men were interned in Rimini, on the Adriatic coast of Italy.

From late 1946 the provisions of the Yalta Conference began to be put into effect. These entailed the return to the Soviets of any prisoner of war in US or UK hands who could be classified as a Soviet citizen. Many thousands, including a large number of Cossacks who had fought against the Soviets during the war, were handed over to face a swift death by firing squad or a slow one in Siberian labour camps. At the prompting of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Pope Pius XII appealed to the western allies to spare the survivors of the 1st Ukrainian Division the same fate, describing them as "good Catholics and fervent anti-Communists".

As a result the Ukrainians at Rimini had their status changed from "prisoners of war" to "surrendered enemy personnel". This may sound a narrow distinction today, but it saved the lives of all of those involved. They were subsequently offered the option of being settled in the UK or in Canada. 7,100 chose to come to the UK, and 1,500 of them arrived in Glasgow on 15 May 1947 on board the troop ship India Victory.

450 of those men were then moved to the disused POW camp at Hallmuir, where most found employment on local farms and forestry projects. Many subsequently settled into the local community. While at Hallmuir the Ukrainians converted the chapel established here by the Italians into a Ukrainian Orthodox Church. After much of the rest of the camp fell into disuse, the landowner gave permission for the chapel to continue in being and to offer services in Ukrainian. It still does so today, and the fact that it remains a place of worship adds a great deal to the atmosphere of the chapel.

The South End of the Chapel, 2013 |

|

|

|

Visitor InformationView Location on MapGrid Ref: NY 129 793 What3Words Location: ///doctors.vocals.heartache |

The Rear of the Chapel, 2013 |

The Rear of the Chapel, 2023 |

New Roof, 2023 |

Shrine Outside the Chapel, 2013 |

Ukrainian Memorial, 2013 |

Floral Wreath, 2023 |

Oblique View of South End, 2013 |